Inside "Drawing Codes"

POSTED ON: January 30, 2019

Drawing Codes, an exhibition that explores forms of representation—whether using hand or computational software—closes Sunday February 24 in the Arthur A. Houghton Jr. Gallery. Subtitled, "Experimental Protocols of Architectural Representation, Volume II," it is the second iteration of an exhibition that originated at the Digital Craft Lab in San Francisco’s California College of Art (CCA).

The show’s curators, architects Andrew Kudless and Adam Marcus, invited 24 architects to submit drawings that adhere to a set of parameters determined by the curators. During a tour of the exhibition on January 29, the two explained that participants were asked to interpret the word “code” as referring to language, script, cipher, or building code—and frequently a combination of two or more. As a historic example, they pointed to the work of Hugh Ferriss, a draftsman who, in a famous set of drawings, illustrated the potential impact of the 1916 Zoning Resolution designed to prevent skyscrapers from blocking light on city streets.

The two curators, each of whom has an architectural practice in addition to teaching, began planning the exhibitions about three years ago. They first hit upon the idea of the show when they realized that their students at CCA associated computational software with Gehry-style buildings testing the limits of materials. Claiming they were uninterested in such deconstructivist designs, they largely ignored the generative possibilities of softwares like Grasshopper.

“It was like saying you don’t want to design a house like Frank Lloyd Wright, so you’re not going to use a pencil,” Mr. Kudless said during a recent visit to Cooper’s Houghton Gallery.

Referring to Columbia University’s paperless studio—started by then-Dean Bernard Tschumi to encourage students to use the most up-to-date digital technology in architecture—Mr. Marcus described current debates on drawing that raise a number of questions that would have been unthinkable before the advent of computer-aided design software: Why make drawings? And if they’re important, are there ways to engage computation in drawing itself, that is, as a generative tool, not just as a means of production?

To explore those questions, they asked the invited architects to consider “how rules and constraints inform the ways architects document, analyze, represent, and design the built environment.” Naturally, that meant they had to impose a set of rules on their participants: drawings had to be done in black and white and printed at 25” x 25,” in addition to offering commentary upon some aspect of the term “code.”

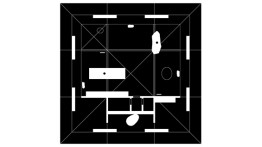

With that in mind, several architects responded by thinking about the role of computer code such as GPS or standard operations in word processing such as cut-and-paste. That last animated the drawing by Outpost Office, the firm of Ashley Bigham and Erik Herrmann. They wondered what the repetition of an image would do to its legibility. They used an iconic image, the plan of the Villa Rotonda by Palladio, and used a computer code to repeat its four outer patios multiple times, making that element smaller with each repetition. The exercise, they cheekily noted in the show’s catalog, demonstrates that “dumb algorithms applied to old drawings offer something completely new….We know. It’s too easy, too clever, too reductive. But we still love it. And we made you look.”

Other participants referred to art forms outside of architecture. Jenny Sabin’s “Convergence” (2018) brings the binary aspect of weaving—the warp and the weft—and relates it to the binary of zeros and ones at the heart of computing. The result is a drawing reminiscent of textiles made by algorithms interpreting color and sound. (She has converted these drawings into rugs using a digitized Jacquard loom, though none are part of the Drawing Codes show.)

A drawing by Cooper’s Dean of the Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture Nader Tehrani and Matthew Waxman entitled “The Synthetic Code” commented on changing methods of representation over the last thirty years. Noting that his is the last generation of architecture students to be taught hand drawing alone, Dean Tehrani set out to make a drawing that, instead of focusing on patterns of arranging bricks—a traditional way of thinking about masonry construction—shows how computer code can lead to alterations in the bond itself. The result is “customized mortar lines that are respondent to scale and the introduction of light and air through the wall section.”

At the tour in January, Dean Tehrani said that hand drawing and using the computer as a generative tool requires what he called “two very different intellectual modalities,” both a necessity. “Today architectural minds need to be more ambidextrous.”

Drawing Codes runs until February 23 when it will travel to the University of Virginia.