Cooper Volunteers Use New Maker Lab to Support Health Workers

POSTED ON: May 7, 2020

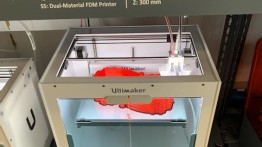

With 3D printers buzzing 24/7 in Cooper’s brand-new fabrication lab, staff and faculty volunteers have organized a state-of-the-art production line to supply protective face shields to health workers. The volunteer group, comprised of members from all three of The Cooper Union’s schools and various departments, came together last month through a tremendous cooperative effort to fabricate a total of 1,500 face shields for New York City hospitals inundated with COVID-19 patients.

“We began by asking how we could use the tools that were at our disposal,” explains Harrison Tyler, director of Cooper’s new Art, Architecture, Construction, and Engineering (AACE) Lab. “While there are many different ways we could’ve made an impact,” Tyler says, “we chose to do something that is really specific to the new technologies we have in the AACE Lab, and we’ve been able to use those technologies in a way that’s very efficient and safe.”

Thanks to a $2 million leadership grant from the IDC Foundation, the first phase of the AACE Lab launched in February, just before the virus hit New York. The lab was conceived as an interdisciplinary maker space, providing the Cooper community with access to a wide variety of computational design and advanced fabrication tools. “Because we had already launched prior to everything going remote, the AACE Lab was set up and ready to go,” Tyler says. “We were ready to handle a high level of output.”

As the city entered lockdown in early March and hospitals began facing shortages of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), Natalie Brooks, Cooper’s Chief Talent Officer, wanted to find out how the institution could support relief efforts. She contacted Tyler and several other community members who had technical experience in fabrication, including Austin Wade Smith, an adjunct instructor in The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture. Smith happened to be involved with an organization called NYC Makes PPE, which was set up by the nonprofit Hack Manhattan to distribute PPE donations from people with access to manufacturing technology.

“I was already plugged into this citywide PPE distribution system,” says Smith. There was great enthusiasm from members of the Cooper community to volunteer and donate supplies, he explains, but the question of what to make and how to do it while observing proper social distancing and safety precautions was more complex: “The difficult part early on was finding the right design for Cooper to make, one that was field-tested and effective.”

Cross-disciplinary assistance in the design process came from two members of the Albert Nerken School of Engineering: Doug Thornhill, laboratory and technician manager for mechanical engineering, and Eric Lima, professor of mechanical engineering and director of the Open-Source Hardware Laboratory. Marget Long, manager of the Paul Laux Digital Architecture Studio and an adjunct instructor in the School of Art, and Emmy Mikelson, manager of technicians in the School of Art, also lent their expertise and hands-on experience.

According to Tyler, certain forms of PPE—such as N95 respirator masks—require more stringent compliance standards in the manufacturing process. “Our decision of what to make was a mix of wanting to use the tools we have available and landing on a design that’s widely accepted and would make a difference,” he says. Initially, the group considered face masks that could be manually assembled by volunteers at home, in isolation, but using the AACE Lab’s tools to produce face shields in bulk had other advantages, such as ensuring all materials are properly disinfected.

“Interoperability is an important factor in the PPE manufacturing ecosystem right now,” Smith says. The face shield design that the group ultimately settled on uses interchangeable components, consisting of an open-source 3D-printed headband attached to a laser-cut transparent shield, an approach that has been adopted by many of the other maker spaces donating supplies. “If we could only get enough plastic to make one part,” he explains, “it would still work with what other people are making in the community.” Through NYC Makes PPE, which acts as a centralized clearing house, the face shield components are delivered from various institutions and maker spaces around the city, matched up, sterilized, and distributed to hospitals in need.

Because demand for PPE materials has soared, sourcing them was one of the biggest hurdles for the group. With generous backing from an anonymous donor who stepped in to help fund the material costs, Smith and the team were able to secure enough plastic to meet the group’s production goal of 1,500 face shields. “When we hit sourcing roadblocks, we moved through the problem in the usual can-do Cooper spirit,” says Long, who along with Thornhill and Mikelson has helped with running 3D printers and laser cutting. “Everyone in our collaborative group was amazingly creative, generous, and flexible.”

That sense of cross-departmental teamwork has enabled the group to work effectively while in isolation, staggering operations so that only one person is on-site in the AACE Lab at a time. “Cooper is manufacturing these face shields 24 hours a day,” Smith says. He explains that the group runs nine 3D printers around the clock, scheduling volunteers to go into the lab throughout the week to switch out the prints, laser cut shields, and sterilize and package the parts. Smith and Tyler have also been developing video training resources to remotely assist volunteers with operating the tools. “It’s been a bit of a challenge because there’s a wide range of backgrounds,” Smith says. “People want to help, so we’ve been making sure individuals with any skill level or familiarity can watch the video and learn how to contribute.”

Tyler says this experience working virtually may also inform the kind of learning that takes place in the AACE Lab down the road, particularly if the need for social distancing and remote learning continues. “It plays into the larger question of what higher education and making look like in this new normal. This is the beginning of seeing how that works and understanding what the challenges are for us.”

Steven Hillyer AR'90, Director of The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture Archive, and his husband Tim Marback, Producer for the Great Hall, have both been volunteering their time despite being newcomers to the AACE Lab. “Neither Tim nor I are well-versed in using fabrication lab equipment,” Hillyer says, “so our focus moved to separating, cleaning, and sterilizing the head brackets that were printed in groups. This has been a highly organized effort, across the disciplines of architecture, art, and engineering. I love that Cooper Union is doing something to give back to the city of New York and its first responders, and I hope this is just the beginning of that kind of thinking.”

Members of the Buildings and Grounds, Office Services, and Security staff have all been instrumental as well, cleaning the AACE Lab between volunteer shifts, delivering materials, and monitoring access to the building. “Natalie Brooks has made sure we have CDC-level sterilization,” Smith says. “The AACE Lab has to be the cleanest space at the school because what we produce needs the highest level of hygiene, and there’s very limited access to that room. Security has to approve it.”

“Harrison might laugh, but I think it’s fair to say this has been the real launch of the AACE Lab,” he adds. For his part, Tyler agrees the collective effort has been a testament to both the ingenuity of the Cooper community and what the AACE lab is capable of producing. “If you look at all of the folks involved in this, there’s representation from architecture, art, engineering, administration, facilities,” he says. “It's really a school-wide effort and it's led by people who are really passionate about what they do and about coming together to make this happen.”