Collaborating in New Spaces

POSTED ON: September 7, 2018

Sam Keene, associate professor of electrical engineering, Albert Nerken School of Engineering I Photo by Marget Long

Though a word suggesting unity is in the school’s name, The Cooper Union is historically

discipline-centric, with each of the three distinct schools developing pedagogy independently. Students take humanities and social science courses together, but that is the extent of their formal crossover. Art, architecture, and engineering share principles—design, making, critical thinking—and practitioners of the three subjects often collaborate in industry, so why not in this setting? One faculty member has taken steps to change that. Sam Keene, associate professor of electrical engineering, conceptualized and taught two cross-disciplinary courses in the spring 2018 semester, bringing architects, artists, and engineers into the same classroom with shared learning goals.

Keene has been a member of the Albert Nerken School of Engineering faculty since 2009. He has had a wide range of research interests, including wireless communication and networks, signal processing, machine learning, and data science. While pursuing his doctorate in electrical engineering at Boston University, he tacked on an interdisciplinary certificate in computational science. You could liken his inquisitive mind to that of Peter Cooper, who balanced multiple curiosities and turned them into inventions and innovations. In fact, one of Keene’s first forays into multidisciplinary teaching was in a subject related to Peter Cooper’s past: beer brewing. Peter Cooper’s father built two breweries up the Hudson River in the early 19th century and the young Cooper learned the trade from him.

In the fall of 2016, Keene pitched the idea of a class in fermentation science to Richard Stock, dean of the school of engineering. The idea in itself was interdisciplinary, as Keene would be exploring processes of chemical engineering, from fundamentals of water chemistry to microbiology and yeast health. But Keene was also interested in covering the history of brewing alongside recent brewing innovations and entrepreneurship. The course was classified as an independent study open to students of all three schools. Four students enrolled from the mix of backgrounds Keene was hoping for—art, architecture, and chemical and electrical engineering.

The success of this experiment prompted Keene to develop courses that were formally cross-listed in different schools. Like his brewing course, the new classes would be project-based rather than discussion- and-task centered. “This ensures students are not just learning alongside each other, but learning from each other,” he says. “They bring different skills to this experience and make for a more stimulating environment.”

Keene took another element of Peter Cooper’s life for a course concept—social justice. The course would educate Cooper students to solve real-world, data-oriented problems in education, equality, justice, health, public safety, economic development, and other areas. By partnering with nonprofits, social enterprises, and government agencies, students would learn to apply data-science, machine-learning, and software-engineering principles to problems that have significant social impact.

Team from Keene's courses displayed their projects at this year's Annual Student Exhibition I Photo by João Enxuto

Team from Keene's courses displayed their projects at this year's Annual Student Exhibition I Photo by João Enxuto

This time, Keene brought his idea straight to President Laura Sparks. Through a contact of Sparks, Keene was connected with Will Shapiro, the founder and chief data scientist of Topos Inc., a company using artificial intelligence to understand cities, as a potential co-instructor for the course. It turned out that Shapiro was himself a 2013 graduate of The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture. Shapiro’s unique background in architecture and data science— he also studied mathematics at Brown University and Cambridge University—was a serendipitous match. Additionally, Shapiro was already on the architecture adjunct faculty. “Will was crucial to recruiting architects for the course and brought a perspective of thinking about space in a certain way that I do not have,” Keene says. They received support from Dean Nader Tehrani and Associate Dean Elizabeth O’Donnell to cross-list the course in the school of architecture as Data Science for Social Good.

Keene, with the help of the Robin Hood Foundation, recruited six nonprofits as clients for the class. In intentionally formed multidisciplinary groups, students used data from the clients combined with open data sets to provide a fresh look and make comparisons. “It ended up as more of an exploration of their data than solving a problem,” Keene admits. “It was hard to dive in deeply with only one semester. But each group ended up providing a helpful observation from the data that we hope the client will utilize.”

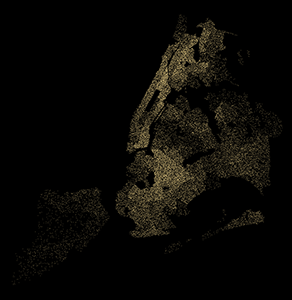

Two groups worked with data sets provided by clients City Harvest and FeedNYC, organizations dedicated to eliminating food insecurity in New York City. Their data sets included historical and geographical information on food facilities and details on the people served. To help City Harvest plan for new facilities, students developed a machine-learning model that predicted the turnout at a new location prior to the facility being built. A group also studied the data to find “food islands,” or networks of different facilities close enough to each other that, when combined, can provide food to nearby populations seven days a week. Finally, students mapped areas of food insecurity using Geographic Information Software. They compared information on food need versus existing food availability to visualize food deserts. Using a CNC milling machine, an architecture student also built a physical model of this representation.

Dot density map showing the food insecure population within each defined neighborhood. Every dot represents 100 people missing food.

Dot density map showing the food insecure population within each defined neighborhood. Every dot represents 100 people missing food.

Keene hopes to continue some of the partnerships and expand research. He is considering pursuing a National Science Foundation grant to keep the class going. “It was a win-win-win situation,” he says. “Students gained experience in this type of work, expanding job pursuits for some; it raised the profile of The Cooper Union as an institution, and it helped a nonprofit organization.”

Meanwhile, Keene was cooking up his other idea. (Yes, he created two new cross- disciplinary courses in vastly different subjects over the course of six months.) He worked with electrical engineering students on a potential machine-learning art exhibition last year, but the idea fizzled. Keene wanted to resurrect the concept but as a class that would provide structure and a much-needed artistic collaborator. Through another Cooper connection, Trustee Kevin Slavin A’95, Keene met Ingrid Burrington, an artist and writer interested in co-teaching the course. “I realized I had no idea how to grade art!” Keene says. “Ingrid was essential for her knowledge and teaching experience.”

The class, named Machine Learning and Art, was a free exploration of the intersections between those disciplines. Students explored and translated complex concepts into creative projects. One assignment involved using machine-learning methods to transform a piece of media from one form to another. George Ho, an engineering student who took both courses as a junior, altered a photo of Peter Cooper in multiple ways. Using different algorithms, he transformed the static Peter Cooper into a moving image who crosses and rolls his eyes.

Keene and Burrington required that many projects be presented in analog form, challenging students to think beyond creating something digitally. An open-ended final project was completed in larger groups. From the start, he planned to have students present their final projects in Cooper’s annual student exhibition. “Engineering classes aren’t conceived with the idea of presenting in the show; we made sure this one was,” Keene says.

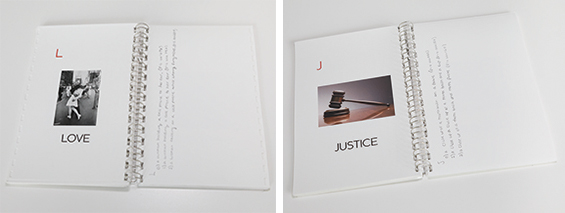

Final project examples included a Jeopardy! game where the machine estimated the value of each trivia question and an edition of the Cooper Pioneer student newspaper in the year 2040 where each article was seeded with a few words and then machine-generated. One group created an A-Z letter book, akin to a children’s book. For each letter, the students chose a popular word and an image that represented that word. They ran each image through a machine-learning algorithm to provide captions. The resulting captions show the difference between the word the students associated with the photo, and what the computer saw.

To make the class happen, Keene met with Mike Essl, dean of the School of Art, who shepherded the course through the curriculum committee. It was classified as an elective course, which Keene learned was problematic for recruiting students. Of the 130 credits art students need to graduate, 54 are studio credits. “I had a lot of students drop the course when they realized it wouldn’t count toward their studio credits. In fact, the art students who remained in the course had all their elective credits already, so taking the class didn’t meet any graduation requirements.”

Keene also learned about the different, but just as important, meaning of “studio” for architecture students and how it affected enrollment in his Data Science for Social Good course. He watched architecture students drop the course when they realized they couldn’t balance the workload with their studio-time commitments.

These weren’t the only road-blocks he encountered. Both of his classes had to be scheduled in the evening to accommodate the adjunct instructors’ work schedules. Team teaching was also time-consuming, especially for a brand-new course. “It involved coordination with your partner on every detail,” Keene says.

Yet the feedback he received from students in the courses has encouraged him to continue offering courses of this nature. “I think the biggest takeaways were how to coordinate with and manage team members who had vastly different skill sets than my own,” George says. “The artist and architect on my team added value to the projects in a way that I couldn’t, simply because I can’t do what they do: I haven’t been trained to think like a designer, I’ve never put up an exhibit before, I’ve never used Photoshop or InDesign in my life. By the same token, the artist and architect can’t do what I do: they have no idea what NMF is, they’ve never run an SQL query, they couldn’t use UNIX command line utilities to format a 2GB csv file. I think that this is the point of the interdisciplinary work: people from different backgrounds, trained in completely different fields, should be brought together to attack one problem.”

While Keene’s courses are prime examples of intentionally and formally mixing students, inter- or cross-disciplinary work does occur organically at The Cooper Union. Each school has a list of classes open to students from other schools; civil engineers frequently take architecture courses and you can find architects in hand-drawing classes for artists. Collaboration has also happened in surprising ways. This spring, Lucy Raven, an assistant professor, found her Audiovisual I class, a prerequisite for moving- image studio classes in the School of Art, to have predominantly fourth- and fifth-year school of architecture students. “They were older students with a sophisticated vocabulary and were well into their coursework, but, like the younger art students, they were more or less new to making moving-image work, as well as to cinema analysis and artists’ moving-image theory and history,” Raven tells us. “Here, the prevalence of architects led me to consider the structure of teaching the moving image in relation to more-literal ‘structures’—buildings and infrastructure, both physical and virtual.” She witnessed the artists and architects learning and growing from each other, both in presentation techniques and critique styles.

Sparks has shown her support for creating more cross-disciplinary opportunities at the institution. As is evident from some of the challenges Keene faced, there is still a great amount of work to do to change the learning landscape, but shifts are happening. In early 2018, The Cooper Union received a $2 million grant from the IDC Foundation to create a multidisciplinary laboratory for all three schools [see sidebar]. Through the Community Planning Collaborative, a volunteer group of faculty, staff, alumni, and students providing feedback on strategic-planning efforts, a working group was created to examine the structural and logistical barriers to interdisciplinary education. Unsurprisingly, Keene is at the helm of this group. The group will propose solutions that respect the distinct characteristics of each school, but work toward providing additional opportunities for cross-disciplinary work.

This fall, Keene is offering his fermentation-science course again, but this time it is not listed as an independent study. Students can enroll in EID334: The Science and Art of Brewing. Keene says having a course number “makes it more official” and affirms his hope that the lines between the schools will continue to blend.